Anuccheda 19

Introduction to Jīva-tattva

The jīva, or the individual self, is counted among the attendants of Paramātmā.

Its extrinsic characteristic (taṭastha-lakṣaṇa) was stated earlier [in Anuccheda 1] in sb 5.11.12, namely, that it is the conditional knower of the presentational field of its own

body-mind complex.

The intrinsic characteristics (svarūpa-lakṣaṇa) [of the jīva] were imparted by Śrī Jāmātṛ Muni, a very senior teacher of the Śrī Vaiṣṇava Sampradāya in the line of Śrī Rāmānujācārya, who has followed the Padma Purāṇa, where it is said in the course of explaining praṇava (Oṁ):

The letter m [in Oṁ] signifies the jīva, “the witness of the presentational field of the body” (kṣetrajña), who is always dependent upon and subservient to the Supreme Self, Paramātmā. He is [constitutionally] a servant of Bhagavān Hari only and never of anyone else.

He is the conscious substratum, endowed with the attribute of knowledge. He is conscious and beyond matter. He is never born, undergoes no modification, is of one [unchanging] form, and situated in his own essential identity (svarūpa).

He is atomic [i.e., the smallest particle without any parts], eternal, pervasive of the body, and intrinsically of the nature of consciousness and bliss. He is the referent of the pronoun “I,” imperishable, the proprietor of the body, distinct from all other

jīvas, and never ending. The jīva cannot be burnt, cut, wetted, or dried, and is not subject to decay. He is endowed with these and other attributes. He is indeed the irreducible remainder (śeṣa) [i.e., the integrated part] of the Complete Whole.

(Padma Purāṇa, Uttara-khaṇḍa 226.34–37)¹

The ātmā is neither god, nor human, nor subhuman, nor is it an immovable being [a tree, mountain, and so on]. It is not the body, nor the senses, mind, vital force, or the intellect. It is not inert, not mutable, nor mere consciousness. It is conscious of itself and self-luminous; it is of one form and is situated in its own essential nature.

It is conscious, pervades the body, and is intrinsically of the nature of consciousness and bliss. It is the direct referent of the pronoun “I,” is distinct [from other individual selves] in each body, atomic [i.e., the smallest particle without further parts], eternal, and unblemished.

It is intrinsically endowed with the characteristics of knowership [cognition], agency [conation], and experiential capacity [affectivity]. Its nature by its own inner constitution is to be always the unitary, irreducible remainder [i.e., the integrated part] of the Complete Whole, Paramātmā.²

This explanation is given in accordance with the commentary of Śrī Rāmānuja on the Brahma-sūtra. Of these characteristics, the first, that the jīva [i.e., the ātmā] is not a god, a human, or any other species of life, was implied in Tattva Sandarbha

(Anuccheda 54) from the following verse:

Just as the vital force (prāṇa) remains unchanging as it accompanies the individual living being( jīva) in whichever different species it may appear, whether born from eggs, wombs, seeds, or perspiration, the ātmā is unchanging in the state of deep sleep when the senses and ego are deactivated and there is freedom from the subtle body, which is the cause of transformation.

Yet, upon awakening, the remembrance comes to us that we slept peacefully without awareness of anything [and this indicates that in deep sleep the self is present as pure witness devoid of the content of sensual, mental, or egoic awareness].

(sb 11.3.39)³

The second characteristic, that the jīva is distinct from the body, the senses, and so on, is stated by Bhagavān Śrī Kṛṣṇa:

The ātmā, which is the witness and self-aware, is distinct from the subtle and gross bodies, in the same way that fire, which burns and illumines, is different from the wood that is burnt.

(sb 11.10.8)⁴

The reason the ātmā is distinct [from the subtle and gross bodies] is that he is their witnessas well as their illuminator, butthe ātmā itself is self-aware(sva-dṛk), meaning it is self-luminous.

Commentary by Srila Satyanarayana das Babaji:

Up to this point, Śrī Jīva has described the ontology of Paramātmā. In doing so, he has explained Paramātmā’s three manifestations as the supreme regulator of the metacosm, the macrocosm, and the microcosm and also His identity among the trinity of gods. Paramātmā is the regulat of the innumerable jīvas and of material nature (prakṛti). To understand the regulator, it is necessary to understand the regulated, just as to understand a manager one also needs to know his field of action. As such, realization of the jīva precedes that of Paramātmā.

Śrī Jīva began his entire discussion of the knowable (prameya) with the famous vadanti verse (sb 1.2.11), cited first in Tattva Sandarbha (Anuccheda 51). His exposition of the knowable has continued right through the Bhagavat and Paramātma Sandarbhas. On the basis of contextual correlation (prasaṅga-saṅgati), in which succeeding topics are auxiliary to preceding ones, Śrī Jīva took up the discussion of Paramātmā first and not that of the jīva. For this reason, he now begins a new topic, delineating the essential nature and qualities of the jīva, beginning with this anuccheda and continuing to Anuccheda 47.

Śrī Jīva begins by first citing four verses from Padma Purāṇa, which describe the nature of the jīva. He then quotes four more verses of Jāmātṛ Muni, which paraphrase the Padma Purāṇa verses. Rāmya Jāmātṛ Muni (1370–1443) was a follower of Rāmānujācārya and popularly known as Varavara Muni. He was also called Mānavāla Mahāmuni and was the founder of one of the Śrī Sampradāya’s two main sects, the Teṅgalai School. We have not been able to trace the exact source of these verses.⁵

In the upcoming anucchedas, Śrī Jīva analyses the statements of Jāmātṛ Muni and provides supporting references from Bhāgavata Purāṇa. Why does Śrī Jīva prefer Jāmātṛ Muni over Padma Purāṇa when Jāmātṛ virtually repeats the words of the Purāṇa?

In the upcoming anucchedas, Śrī Jīva analyses the statements of Jāmātṛ Muni and provides supporting references from Bhāgavata Purāṇa. Why does Śrī Jīva prefer Jāmātṛ Muni over Padma Purāṇa when Jāmātṛ virtually repeats the words of the Purāṇa?

Our guess is that Jāmātṛ adds three characteristics that are not stated there explicitly, namely, knowership (cognitive awareness), doership (conation), and experiential capacity (affectivity). The Advaita Vedāntīs do not accept these three as inherent capacities of the jīva, intrinsic to its very nature. Rather, they view them as limiting adjuncts (upādhis) of the self, having empirical validity only. These views stand diametrically opposed to the core teaching of theistic Vedānta, or in other words, of the Vaiṣṇavas, including Jīva Gosvāmī. For Vaiṣṇavas it is crucial to acknowledge the jīva as eternally distinct from and subservient to Paramātmā. For this to be possible, the jīva must be inherently endowed with knowership, agency, and experiential capacity.

An object has two types of defining characteristics (lakṣaṇa), called taṭastha and svarūpa. The purpose of defining the characteristics of an object is to distinguish it from others, both similar and dissimilar, in order to determine how to deal with it appropriately (vyāvṛttir vyavahāro vā lakṣaṇasya prayojanam). Taṭastha, extrinsic or incidental defining characteristics, are those that are identifiable as extraneous to the object being defined, which do not belong to its essential nature but by which it is commonly recognized. Svarūpa characteristics are those that are part of the object itself, essential, and intrinsic to it.

The taṭastha characteristics of the jīva were given in sb 5.11.12, as cited in Anuccheda 1. There it was said that the jīva is conditioned by the mind and thus bound to the material world. The pure, unbound, unconditioned being is called the ātmā, whereas the conditioned being is called the jīva. The cause of conditioning is the beginningless ignorance (anādi avidyā) of the self ’s real identity, or svarūpa, which results in absorption in the mental modifications (citta-vṛtti).⁶ In this anuccheda, Śrī Jīva begins a description of the jīva’s svarūpa. Different schools of Indian philosophy have different concepts of the jīva. A summary of these views is presented here:

- The Cārvāka, or Lokāyata, School.

- Buddhism

- Jainism.

- Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika.

- Mīmāṁsā.

- Yoga and Sāṅkhy

- Advaita Vedānta.

The Cārvāka, or Lokāyata, School. There are no original works of this school available at present. Whatever is known about it is concluded from other schools who cite its views as pūrva-pakṣa and refute them. The Sarva-darśana-saṅgraha of Madhvācārya, a work belonging to the 14th century, provides a summary of the school in its first chapter. Prabodha-candrodaya (Act 2), an allegorical play, also depicts the salient features of the school. Ṣaḍ-darśana- samuccaya, an eighth century work by Haribhadra Suri, also summarizes the doctrines of this school. Reference to Lokāyata follow- ers is also found in the old works of Buddhism, such as Dīgha-nikāya (1) and Majjhima-nikāya (1). Bṛhaspati-sūtra was supposed to be the original text of the Lokāyata School.

The Cārvāka School considers the body-mind complex itself to be the self. There is no ātmā, or self, separate from the body. Cārvāka holds that consciousness is an epiphenomenon, the outcome of the combination of material elements. They admit only four elements (tattva), namely, earth, water, fire, and air. It is a doctrine based exclusively on sensory data. Therefore, they do not acknowledge the existence of ether, the ātmā, and God. The elements are considered eternal but their combinations undergo different modifications and dissolution. Consciousness is a by- product of matter. It is produced when the elements combine into a particular coalescence, although the elements separately do not possess it, just as fermented yeast produces an intoxicating quality.

In the Cārvāka realism, consciousness is observed to be associated with the body, and it disappears when the body disintegrates. The ātmā is just the conscious living body. The pronoun “I” refers to the empirical self. One uses the pronoun “I” to refer to the gross physical body when one makes statements, such as, “I am fat,” “I am thin,” “I am weak.” This is because the body alone is the true self. As such, it is very dear to all beings, and they try to protect it at any cost. A person can sacrifice anything for the sake of his body. It is also said:

One should abandon a family member to protect the whole family, sacrifice a family for the sake of a village, disown a village to safeguard a district, but to protect the self (the ātmā), one should give up the whole earth. (Pañcatantra 1.386)⁷

The Cārvāka School avers that the word ātmā (self ) in this verse is used for the body. According to Siddhi-traya (12) of Yamunācārya, there are various theories of ātmā within the Lokāyata School. Some consider the ātmā as the gross body, others as the senses, the mind, or the vital air. Because we do not have access to the original works of the school, it is hard to say what exactly their view entailed. The knowledge we have is only from the works of other schools who may have addressed only the weakest points in their metaphysics with a view to refute them.

From the name Lokāyata, it appears that their philosophy was materialism, like the modern scientists who treat consciousness as a by-product of the body. Dr. Radhakrishnana writes, “Lokāyata, directed to the world of sense, is the Sanskrit word for materialism.”⁸ The seed-conception of materialism can be found in the Upaniṣads. For example, the Taittirīya Upaniṣad says: “Indeed, this body, made of the essence of food, is the self (ātmā)” (tu 2.1.1).⁹

In Bṛhad-āraṇyaka Upaniṣad, the sage Yājñavalkya says: “A husband is not dear for the sake of the husband, but for the sake of the ātmā” (bau 2.4.5).¹⁰ According to the Cārvāka School, the word ātmā here refers to the body of the husband because the wife loves the husband’s body, not something invisible beyond the body. If one objects that the wife does not love the dead body of her husband,

Cārvāka replies that this is so only because the consciousness in the body ceases to function. Death for them means that consciousness, which is a by-product of the body, comes to an end. In Viṣṇu Purāna (3.18.3–31), we find Māyāmoha’s instructions to the Daityas, which conform to materialism. Similar instances are found in Rāmāyaṇa and Mahābhārata (Śānti-parva). This philosophy of the ātmā’s being equated with the body, the senses, the mind, or the vital air has been refuted in Tattva Sandarbha (Anucchedas 53–60).

Buddhism. Gautama Buddha, the founder of the school, does not make any definitive statement about the ātmā’s existence. He spoke of five khandhas (skandhas), or aggregates, which constitute the body and mind of all sentient beings. The pronoun “I” may refer to any one of these or all of them collectively. These include:

- Rūpa, or form, consisting of the four primary elements — earth, water, fire, and air — which provide corporeality to the body and senses.

- Vedanā, or feelings, in the form of pleasure, pain, and indifference, arising out of contact with the five senses and the mind.

- Sañña (sañjñā), or conceptual knowledge or perception, related to the five senses and the mind.

- Saṅkhāra (saṁskāra), or volitional states, in connection with form, sound, smell, taste, touch, and mental objects.

- Vijñāna, or consciousness, also related to the five senses and the mind.¹¹

As regards Buddha’s view on the ātmā, Dr. Radhakrishnana writes:

While agreeing with the Upaniṣads that the world of origination, decease, and suffering is not the true refuge of the soul, Buddha is silent about the ātman enunciated in the Upaniṣads. He neither affirms nor denies its existence. […] Buddha contents himself with a psychical phenomenon, and does not venture to put forth any theory of the soul. […] To posit a soul seemed to Buddha to step beyond the descriptive standpoint. What we know is the phenomenal self. Buddha knows there is something else. He is never willing to admit that the soul is only a combination of elements, but he refuses to speculate on what else it may be.¹²

The reason for Buddha’s ambivalence in regard to the ātmā is that he disregarded the Vedic authority and sought to establish his path exclusively on the basis of experience and logic. However, the later followers of Buddha, like Nāgārjuna, adopted a definitive stand on the ātmā’s non-existence in exclusion of the five skandhas.¹³

There are various schools of Buddhism having different opinions about the objective world and its perceiver. One of the most popular is called Vijñānavāda or Yogācāra, regarded as a form of subjective idealism. This doctrine holds that consciousness alone exists and fluctuates at every moment. Every phenomenal appearance is momentary. Everything that arises out of causes and conditions is necessarily impermanent. The preceding moment is the cause of the succeeding moment. Change is the law of the universe. External objects do not exist outside of thought, or ideation. The empirical ego is also unreal. The apparent objects of the world are like a river that flows constantly. There is nothing in the world that is not momentary. Consciousness manifests itself both as subject as well as object. It arises out of its own seed and then manifests itself as an external object. Just as in a dream mental objects are projected out of one’s own consciousness, so too in the waking state, empirical objects are but percepts projected out of the store of consciousness. There is neither subject nor object but only a succession of ideas.¹⁴

Jainism. This school posits that in its pure state, the ātmā possesses infinite perception, knowledge, bliss, and power. It is all-perfect and distinct from the body. The number of ātmās is infinite. The dimension of the self is considered to be neither atomic nor all- pervading. It is medium-sized and determined by the magnitude of the body it inhabits. The ātmā occupies the whole of the body. It is of very small size when it originates in the womb but goes on expanding as the body grows in size. In each successive transmigration, a particular jīva contracts or expands in its magnitudinal proportions. A bound self is vitiated by subtle particles of fine matter (karma) that accrue to a jīva due to its former actions and intentions. The means through which karma clings to the self is called āśrava, or the influx of karma-matter, which is the effect of bodily, verbal, and mental actions, and is the cause of bondage of the self. This bondage is beginningless.¹⁵

Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika. The schools of Nyāya and Vaiśeṣika share a common view about the ātmā. They both claim that the ātmā is an eternal substance devoid of parts or divisions and bereft of consciousness. Consciousness, therefore, is an incidental quality of the ātmā that arises only when it is in contact with the mind. The ātmā is an all-pervading substance, the substratum of knowledge ( jñāna), or consciousness, and is motionless.¹⁶ These schools do not distinguish between knowledge and consciousness. When a self becomes liberated, which means disconnected from the mind, it remains as an inert substance. The self is a real subject of experience, a real knower, and a real agent. Each self has a manas (or psychic instrument) during its empirical existence and is separated from it in liberation. It is distinct from the body, the senses, and the mind.¹⁷ There is a separate ātmā in each body.¹⁸ Thus, there are an infinite number of ātmās.

Mīmāṁsā. There are two major schools of Mīmāṁsā, one founded by Kumārila Bhaṭṭa and the other by Prabhākara. Both admit the plurality of individual beings and consider the self as an eternal, all-pervading substance that is the substratum of consciousness. The self is a real knower, the subject of experience, and an agent. It is distinct from the body, the senses, the mind, and knowledge.

Prabhākara, like the Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika School, accepts that the self is essentially unconscious. Consciousness is an incidental property of the self when it is in contact with the mind. Cognition, affect, volition, and agency are the properties of the self and arise due to merit and demerit in its conditioned state. In the liberated state, the self remains as a pure substance divested of its qualities, including consciousness and bliss.

Prabhākara says that the self is merely the substrate of the cognition, “I know,” but not as of the nature of consciousness. If the ātmā were of the nature of consciousness, it would result in the defect of consciousness being both support and supported, or in other words, subject and object. It is everyone’s experience that subject and object are distinct from each other. Therefore, the ātmā must be different from consciousness, implying that it is non-conscious, since consciousness does not constitute its essence.

Kumārila Bhaṭṭa, however, accepts the ātmā as both partly conscious and partly unconscious. He says that in deep sleep, there is both consciousness and unconsciousness. If all knowledge were lost during deep sleep, then one would not remember things on waking up. But such is not the case. Therefore, it must be accepted that there is a stable consciousness in deep sleep and this consciousness — when united with the impressions from past experiences — makes us recognize and recollect. But like Prabhākara and the Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika, Kumārila too believes that in the liberated state, the self remains as a pure substance divested of its qualities of consciousness, agency, and bliss, though he adds that as in deep sleep, the self is then characterized by potential consciousness.¹⁹

Yoga and Sāṅkhya. The schools of Yoga and Sāṅkhya consider prakṛti (primordial nature) and puruṣa (the conscious living being, or self ) as the two fundamental principles of the cosmos. Puruṣa is the principle of pure consciousness, distinct from mind, intellect, ego, body, and senses. It is not merely a substance that possesses consciousness as a quality. Rather, consciousness is its very essence.²⁰ It is the ultimate knower that is the foundation of all knowledge. It is the subject of knowledge and can never become its object. It is beyond time and space, and devoid of any activity or modification. It is eternal and all-pervading. Sāṅkhya and Yoga believe in the plurality of puruṣas.²¹ Bliss is different from consciousness and is a product of sattva-guṇa (prītyātmakaḥ sattva-guṇaḥ). Knowledge is a modification of the mind, called citta-vṛtti.²²

Advaita Vedānta. Advaita Vedānta proclaims that the jīva is nondifferent from Brahman.²³ However, this identity with Brahman is realized only when the jīva transcends the self-identification with its temporary phenomenal body-mind complex. The jīva is of the nature of consciousness, eternal, beginningless, and indestructible. But this reality is the truth of the jīva as Brahman, and not as a separate and independent entity. There are different views among the Advaita scholars as to how Brahman comes to be identified as the jīva. The most prominent among them hold that the jīva is Brahman, either covered by, delimited by, or reflected, in ignorance.

In his Brahma-sūtra commentary (2.3.50), Śaṅkara says, “And the self is only the reflection of the higher ātman.”²⁴ Later this concept became known as pratibimba-vāda (“the theory of reflection”) in the writings of Prakāśātmā and Vidyāraṇya. Śaṅkara offers another explanation about the nature of the self while commenting on Brahma-sūtra (2.3.17). He gives the example of ākāśa (all-pervading space) being divided by various clay pots.²⁵ As long as the pots are present, the one ākāśa appears to be divided. If the pots are removed or broken, the initial unity of ākāśa is reinstated. Even when the pots were present, space was still only one, but it appeared as many in different pots.

In the same way, the one Brahman becomes divided by avidyā, or ignorance. There is only one reality, i.e., Brahman. Brahman or ātman delimited by upādhis is the jīva, who suffers and enjoys in accordance with its acts. When the upādhis are dissolved, the jīva is established in its supreme glory as Brahman, just as one sees a rope as it is when the illusion of its being a snake is dispelled (Brahma-sūtra, Śāṅkara-bhāṣya 1.3.19).²⁶ This theory later became known as avaccheda-vāda (“the theory of limitation”) in the writings of Vācaspati Miśra. Brahman as well as the jīva, or individual self, is neither inert, nor temporary, nor miserable. It is devoid of agency, experiential capacity, and knowership (Brahma-sūtra, Śāṅkara-bhāṣya 2.3.40).²⁷

The above views of the different schools may be summarized as follows. With the exception of Advaita Vedānta, all the other schools acknowledge a plurality of ātmās. Naiyāyikas, Vaiśeṣikas, Sāṅkhyaites, Yaugas, and Advaitavādīs accept the ātmā as all-pervading. The Cārvākas and Jains believe the ātmā to be medium-sized, i.e., as proportionate to the size of the body. Vaiṣṇava Vedānta concludes that the ātmā is atomic in size. Naiyāyikas and Vaiśeṣikas accept agency in the ātmā, while Sāṅkhya and Yoga schools claim that agency is in prakṛti. Advaitavāda avows that the ātmā has agency only because of the external imposition of adjuncts, or upādhis, i.e., in the conditioned state.

Advaita Vedānta is the main obstacle to the path of bhakti, because bhakti is not possible on the basis of the absolute identity between the jīva and Brahman. It is, therefore, important to understand the position of Advaita Vedānta, which Śrī Jīva will attempt to refute. Since he does not state the opponent’s view, we will give a brief summary here.

Advaita Vedānta accepts six elements as beginningless.²⁸ These are the jīva, Īśvara, pure or para Brahman, māyā or avidyā, the relation of avidyā to the jīva, and the relation of Īśvara to avidyā. Of these, Brahman and avidyā are the main principles. An object that always exists in the past, present, and future is called sat, or real (Brahma-sūtra, Śāṅkara-bhāṣya 2.1.16). That which never exists is called asat, or unreal. Avidyā, also called ajñāna or ignorance, is different both from sat (real) and asat (unreal). It consists of three guṇas, i.e., sattva, rajas, and tamas. It has existence, but its exact nature cannot be specified.²⁹ It has two divisions, collective and individual. When Brahman is limited by the collective form of avidyā, it is called Īśvara or God, and when it is delimited by the individual avidyā, it is called jīva.³⁰

Some Advaita scholars say that māyā has two divisions, called māyā and avidyā.³¹ Māyā is predominant in pure sattva and avidyā in impure sattva. Brahman reflected in māyā is called Īśvara, and reflected in avidyā is called jīva.³² Īśvara is the Supreme Controller, the creator of the universe and immanent in it. The jīva is limited in knowledge and under the control of Īśvara. Some Advaita scholars accept only one jīva, while others accept a plurality.³³

A question may be raised, that if Brahman is a self-luminous, conscious being, then how can it lose its luminosity? Moreover, if Brahman is untouched by anything and is indifferent, then how can it create the world? In response to this, Advaita Vedānta says that avidyā has two potencies. One is the potency of concealment (āvaraṇa-śakti) that covers the real nature of an object, and the other is the potency of projection (vikṣepa-śakti) that manifests various avāstava, or illusory, forms. These potencies of māyā have a beginningless relation with Brahman. Consequently, the potency of concealment veils the cit (consciousness) and ānanda (bliss) features of Brahman, and the potency of projection manifests the phenomenal world appearance. The potency of concealment veils only the cit and ānanda features of Brahman and not the sat feature (or the quality of existence). For this reason, the sat feature pervades all objects of the universe. This is experienced by us as “the table exists, the chair exists,” but we do not experience the pervasion of cit and ānanda in the objects of the material world.

One of the basic concepts used by Advaita Vedānta to explain the variety experienced by us in the temporal world, despite the unity of Ultimate Reality, is called the adhyāropa-vāda principle.³⁴ Adhyāropa means superimposition of the non-real (avastu) on the real (vastu). Vastu is that which exists even when we are ignorant of it; avastu, on the other hand, exists only while we are aware of it. For example, to mistake a rope for a snake is an instance of adhyā- ropa. In this example, the rope is the vastu, and the snake the avastu. The snake is superimposed onto the rope, so the rope exists even while misperceived as a snake, but the snake exists only as long as we superimpose “snakeness” upon the rope. When the mistake is corrected, one sees only the rope and not the snake.

The statement “this is a rope,” has two parts, i.e., “this” and “a rope.” When a rope is seen in semi-darkness and misperceived as a snake, the rope part of the perception is veiled by the covering potency of ajñāna (ignorance or misperception). The “this” part of the perception, however, is not veiled, meaning that there is indeed a phenomenal appearance (i.e., the object) present to the perceiving subject. When we fail to perceive that the object present to awareness is in fact a rope and mistake it for a snake, we still experience the “this” part of the perception. In that moment, the vikṣepa- śakti (the projective potency of ajñāna) produces the appearance of a snake, but the “this” part (i.e., the object present to awareness) continues to exist. Therefore, one says, “This is a snake.”

This is analogous to Brahman and phenomenal objects. The potency of concealment covers the cit and ānanda aspects of Brahman, but the sat feature continues. Then the vikṣepa-śakti projects the phenomenal objects and one experiences them as sat, or existent, but devoid of cit and ānanda.

Advaita Vedānta posits three grades of existence (sattā), namely, pāramārthika, or ontological reality, vyāvahārika, or empirical reality, and prātibhāsika, or illusory reality.³⁵ Pāramārthi- ka-sattā can never be lost or negated. The vyāvahārika-sattā is experienced in the empirical state of causally connected spatio-temporal existence, but it is sublated (i.e., set aside as false) in the pāramārthika state of ultimate being. Empirical existence is visible in the pragmatic objects of our daily experience in the waking state. Material objects, which are effects of prior causes, are subject to destruction, but their existence, which inheres in their ultimate support (i.e., Brahman), is not sublated, bādhita. Bādhā means the destruction of an effect along with its cause. In the course of the world manifestation, material objects are destroyed, but their ultimate cause, Brahman, is not destroyed. Therefore, they are called abādhya . The prātibhāsika objects are abādhya only as long as they are misperceived as real, but they are negated as false, or bādhita, at other times. When a rope that was previously misperceived as a snake is later correctly perceived as it is, then the illusory snake along with its cause, i.e., ignorance, is bādhita, or negated.

Brahman is devoid of any qualities, parts, or divisions. When we see a rope, it is actually Brahman covered by the āvaraṇa-śakti of ignorance and projected as a rope by the vikṣepa-śakti of ajñāna. This is vyāvahārika-sattā, or empirical reality. When we perceive a snake in a rope, the āvaraṇa-śakti conceals the rope and the vikṣepa-śakti projects a snake. This is prātibhāsika-sattā, or illusory reality. Brahman concealed by the covering potency of ajñāna manifests as the jīva, or the individual being, and then it projects — upon the jīva — the characteristics of agency, experiential capacity, happiness, misery, delusion, and so on, by the vikṣepa-śakti of ajñāna. Thus, according to Advaita Vedānta, the jīva is not inherently endowed with (or constituted of ) the capacities of knowership, agency, experiential capacity, or qualia (individual instances of subjective, conscious experience). It is mere consciousness. Indeed, it is more appropriate to say that it is not inert.

With the exception of Advaita Vedānta, all the schools described above base their theories primarily on logic. Among them, Advaita Vedānta is the only school that interprets śabda (scriptural revelation), albeit wrongly, to establish its theory of ātmā. Besides the radical interpretation of Vedānta propounded by Śaṅkarācārya, there are Vaiṣṇava schools of Vedānta, such as Viśiṣṭa-advaitavāda of Śrī Rāmānujācārya, Dvaitavāda of Śrī Madhvācārya, Svabhāvika- bheda-abheda of Śrī Nimbārkācārya, Śuddha-advaitavāda of Śrī Vallabhācārya, and Acintya-bheda-abhedavāda of Śrī Caitanya Mahāprabhu.

All these Vaiṣṇava schools consider the theories of the above schools as pūrva-pakṣa and refute them. There are two strategies to counter these theories. One is on the basis of logic alone and the other is through the authority of śabda assisted by logic. In Tattva Sandarbha (Anuccheda 11), Śrī Jīva Gosvāmī rejects the first option, because it is indecisive. He also states that in matters beyond sense perception, śabda is the sole means of valid knowing. More over, even among the various scriptures accepted as śabda, Śrī Jīva argues in favor of Bhāgavata Purāṇa as the ultimate authority.

In Bhagavad Gītā (2.25), Bhagavān Kṛṣṇa includes transrationality (acintyatva) as one of the characteristics of the ātmā. In light of this, Śrī Jīva adopts the second strategy to refute all of the oppositional theories of the diverse schools. Although not stated explicitly, his main opponent is Advaitavāda. There are two reasons for this.

The first is that Advaitavāda bases its theories on the same scriptural revelation (i.e., the Upaniṣads, the Gītā, and the Brahma-sūtra). Thus, it is necessary to point out the limitations and defects in the Advaitavāda interpretation in order to establish the real intent of scripture. The second reason is that Advaitavāda has done an effective job of refuting the other schools. Consequently, if Advaitavāda is refuted, all other views stand defeated. This is known as the principle of conquering the ace wrestler, pradhāna- malla-barhaṇa-nyāya.

In addition to Śrī Jīva Gosvāmī’s elaboration of the intrinsic characteristics of the jīva based on Jāmātṛ Muni’s verses, Anucchedas 37–44 concentrate on the nature of the jīva as an integrated part of Paramātmā and on the jīva’s oneness with and distinction from Paramātmā. Anucchedas 45–47 present various other characteristics of the jīva.

Śrī Jīva Gosvāmī begins discussing sequentially the intrinsic qualities of the ātmā listed by Jāmātṛ Muni. He does so by citing evidence from Bhāgavata Purāṇa. Of these characteristics, the first, that the ātmā is not a god, a human, or any other species of life, mentioned in the first half of Jāmātṛ’s first verse, was implied in Tattva Sandarbha (Anuccheda 54). In this connection, the verse cited by Jīva Gosvāmī (sb 11.3.39) clearly states that the ātmā is distinct from the physical body, being free from modifications and the witness of deep sleep. It is the physical body that assumes various appellations of a deva, a human being, an animal, or an immovable being, such as a tree. For an elaborate explanation of this verse, one should read the commentary on it given in Tattva Sandarbha.

The second characteristic, mentioned in the second half of Jāmātṛ’s first verse, that the ātmā is distinct from the body, the senses, the mind, and the vital air, is confirmed by Śrī Kṛṣṇa (sb 11.10.8). He gives the example of fire and wood. Fire is hidden in wood, but when wood is ignited, fire becomes visible and burns the wood. One can understand from this that fire is distinct from wood. In the same way, the ātmā illuminates the body, the mind, and so on, while remaining invisible. Being inert, the psycho-somatic instruments cannot function without the ātmā. If the ātmā becomes aware of its true nature, it not only illuminates the body-mind complex but also brings to an end its bondage of identification with them.

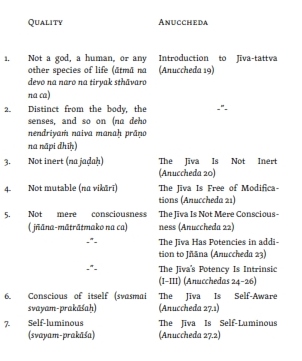

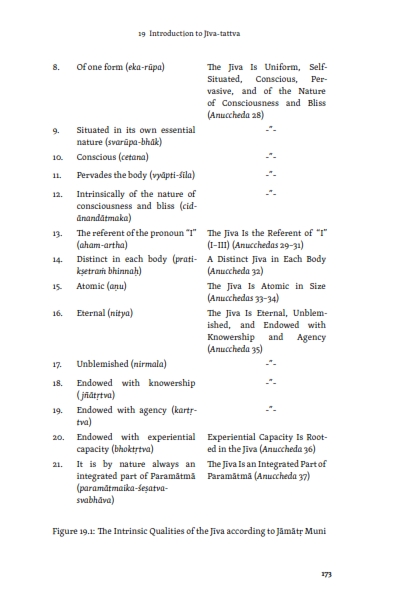

We have inserted the following chart below for consultation purposes and for the reader’s information. It may be observed that many of the verses offered as pramāṇa repeat many of the same characteristics, e.g., “witness,” etc. The intrinsic qualities of the jīva (or the ātmā), as given in the four verses of Jāmātṛ Muni, are listed in the left column, and their corresponding anuccheda headings and numbers appear on the right.

Beginning from the next anuccheda up to Anuccheda 37, Śrī Jīva Gosvāmī discusses the remaining characteristics of the ātmā listed by Jāmātṛ Muni.

_____

¹ jñānāśrayo jñāna-guṇaś cetanaḥ prakṛteḥ paraḥ

na jāto nirvikāraś ca eka-rūpaḥ svarūpa-bhāk

aṇur nityo vyāpti-śīlaś cid-ānandātmakas tathā

aham-artho’vyayaḥ kṣetrī bhinna-rūpaḥ sanātanaḥ

adāhyo’cchedyo hy akledyas tv aśoṣyo’kṣara eva ca

evam ādi-guṇair yuktaḥ śeṣa-bhūtaḥ parasya vai

ma-kāreṇocyate jīvaḥ kṣetrajñaḥ paravān sadā

dāsa-bhūto harer eva nānyasyaiva kadācana

² ātmā na devo na naro na tiryak sthāvaro na ca

na deho nendriyaṁ naiva manaḥ prāṇo na nāpi dhīḥ

na jaḍo na vikārī ca jñāna-mātrātmako na ca

svasmai svayam-prakāśaḥ syād eka-rūpaḥ svarūpa-bhāk

cetano vyāpti-śīlaś ca cid-ānandātmakas tathā

aham-arthaḥ prati-kṣetraṁ bhinno’ṇur nitya-nirmalaḥ

tathā jñātṛtva-kartṛtva-bhoktṛtva-nija-dharmakaḥ

paramātmaika-śeṣatva-svabhāvaḥ sarvadā svataḥ iti

³ aṇḍeṣu peśiṣu taruṣv aviniściteṣu prāṇo hi jīvam upadhāvati tatra tatra

sanne yad indriya-gaṇe’hami ca prasupte kūṭastha āśayam ṛte tad anusmṛtir naḥ

⁴ vilakṣaṇaḥ sthūla-sūkṣmād dehād ātmekṣitā sva-dṛk

yathāgnir dāruṇo dāhyād dāhako’nyaḥ prakāśakaḥ

⁵ Our guess is that the verses are taken from the commentary on some work of

Lokācārya Pillai, who wrote 18 rahasyas (esoteric doctrines) on which Jāmātṛ

Muni has commented.

⁶ See Tattva Sandarbha, Anucchedas 32 and 63.

⁷ tyajed ekaṁ kulasyārthe gramasyārthe kulaṁ tyajet

grāmaṁ janapadasyārthe svātmārthe pṛthivīṁ tyajet

⁸ Indian Philosophy, Volume 1, footnote on p. 279.

⁹ annāt puruṣaḥ

sa vā eṣa puruṣo’nna-rasa-mayaḥ …

ayam ātmā

¹⁰ na vā are patyuḥ kāmāya patiḥ priyo bhavati

ātmanas tu kāmāya patiḥ priyo bhavati

¹¹ Saṁyutta-nikāya 3.86

¹² Indian Philosophy, Volume 1: 387–88

¹³ Based upon Nāgārjuna’s commentary on Prajñāpāramitā-sūtra, cited in Indian

Philosophy, Volume 1, p. 387.

¹⁴ Based on Outlines of Indian Philosophy, Volume 1 (pp. 205–206), and

Sarva-darśana-saṅgraha (Chapter 2).

¹⁵ Based on Outlines of Indian Philosophy, Volume 1 (pp. 188–189).

¹⁶ Tarka-bhāṣā, Uttara-bhāga 78, 91

¹⁷ Based on A History of Indian Philosophy, Volume 1 (pp. 362–363), and

Nyāya-mañjarī (p. 432).

¹⁸ Nyāya-vārttika-tātparya-ṭīkā 1.1.10; Nyāya-bhāṣya 3.1.14

¹⁹ Based upon Śāstra-dīpikā, Ātmavāda, pp. 550–581, and Śloka-vārttikā, Ātmavāda,

pp. 839–884.

²⁰ puruṣas tu sukhādyananuṣaṅgī cetanaḥ.

Sāṅkhya-tattva-kaumudī on Sāṅkhya-kārikā 5

²¹ Sāṅkhya-kārikā 17–20 and Sāṅkhya-tattva-kaumudī on the same.

²² sattva-samudrekaḥ so’dhyavasāya iti vṛttir iti jñānam iti cākhyāyate.

Sāṅkhya-tattva-kaumudī on Sāṅkhya-kārikā 5

²³ tat tvam asi

chu 6.8.7

ayam ātmā brahma

bau 2.5.19

²⁴ ābhāsa eva caiṣa jīvaḥ parasyātmano jala-sūryakādivat pratipattavayḥ. na sa eva

sākṣat. nāpi vastvantaram.

²⁵ buddhyādyupādhi nimittam tvasya pravibhāga-pratibhānam ākāśasyeva ghaṭādi-sambandha-nimittam.

²⁶ yat-paraṁ jyotirupasampattavyaṁ śrutaṁ tat-paraṁ brahma tac

cāpahatapāpmatvādi dharmakaṁ, tad eva jīvasya pārmārthikaṁ svarūpaṁ tat

tvam asi ityādi śāstrebhyaḥ. netarad aupādhi-kalpitam … tasmād yad

avidyāpratyupasthāpitam apamārthikaṁ jaivaṁ rūpam kartṛ-bhoktṛ-rāgadveṣādi-doṣa-kaluṣitam

anekānartha-yogi tad vilayanena tad viparītam

apahatapāpmatvādi viguṇakaṁ pārmaiśvaraṁ svarūpaṁ vidyayā pratipādyate

sarpādivilayaneneva rajjvādīn.

²⁷ tasmād upādhi-dharmādhyāsenaivātmanaḥ kartṛtvaṁ na svābhāvikam.

²⁸ jīva iso viśuddhā cit tathā jīveśayor-bhidā. avidyā tac citor yogaḥ ṣad-asmākam

anādayaḥ.

Source unknown

²⁹ ajñānaṁ tu sāsadbhyām anirvacanīyaṁ triguṇātmakaṁ jñānavirodhi bhāvarūpaṁ

yat kiñcit iti.

Vedānta-sāra 6

³⁰ Saṅkṣepa-śārīraka 3.148

³¹ sattva-śuddhyaviśuddhibhyāṁ māyāvidye ca te mate

Pañcadaśī 1.16

³² See Pañcadaśī 1.17.

³³ See Siddhānta-leśa (1.43–51) of Appaya Dīkṣita.

³⁴ Vedānta-sāra 20–21; Brahma-sūtra, Śāṅkara-bhāṣya 1.1.1

³⁵ Vedānta-paribhāṣā, Pratyakṣa-pariccheda and Śāṅkara-bhāṣya 1.1.14