Tattva Sandarbha

Anuccheda 51

“Absolute Reality Is Nondual Consciousness”

“What is the nature of this Substantive (vastu), which is the AbsoluteReality(tattva)?”

This is disclosed in the following statement:

“All those who have realized Absolute Reality (tattva) refer to that Reality as nondual consciousness (advaya-jñāna)”

(sb 1.2.11).

Here the word jñāna indicates that the Absolute is purely of the nature of consciousness. Additionally, the nondual nature of this Reality is established on the following grounds:

( 1 ) There is no other Reality(tattva), either similar or dissimilar, that is selfexistent;

( 2 )The nondual Absolute is supported only by its own

inherent potencies;

( 3 ) These potencies can have no existence without it as their absolute foundation.

The term tattva, implying here the ultimate good of all that may be attained by human beings, makes it apparent that this tattva, or Absolute Reality, is the embodiment of supreme bliss and is, therefore, also eternal. Śrī Sūta spoke the verse under discussion.

Commentary

In the last anuccheda, Śrīla Jīva Gosvāmī stated that the Absolute Reality is to be known from Śrīmad Bhāgavatam. This naturally raises the question, “What is the essential nature of this Absolute Reality?”

In reply, Jīva Gosvāmī quotes sb 1.2.11, which declares that Absolute Reality is nondual (advaya), or in other words, “one without a second.”

There cannot be more than one Absolute Reality, because if there were a second,

the first would no longer be Absolute, since hypothetically speaking, the second reality could be determined as inferior, equal, or superior to the first one.

If it were either superior or inferior to the first, then only one of them would be Absolute. If both of them were equal, they would compete for supremacy, unless they were found to be always in agreement, which would then make them effectively one for all practical purposes.

That the Absolute Reality is nondual, however, does not mean that nothing else exists. Rather, the word “nondual” indicates two things:

First, the Absolute Reality is self-existent, meaning that it is grounded in itself and depends on no external support; second, nothing else can exist independent of this nondual Reality’s support.

In Vedāntic logic, an object is considered nondual if it is free of three kinds of difference— that among objects of the same class, that among objects of different classes, and that between an object and its parts.

A difference between objects of the same class is called sajātīya-bheda.

Even though two chairs may look the same, have the same function, and belong to the class called “chair,” they still differ as individual chairs. A change in one will not directly affect the other.

A difference between objects of different classes is called vijātīya-bheda.

For example, a chair is different from a table in itsappearance and function.

Finally, a difference between an object and its parts is called svagata-bheda.

If all the parts of a chair are scattered, the chair no longer exists.

For example, the various parts of a chair can be removed and replaced without changing the chair’s identity.

Thus, the parts are independent from each other and from the object, the chair.

In this way, it is evident that the chair is not self-existent.

These three kinds of difference give rise to the duality we observe throughout material nature. They do not exist, however, on the absolute plane; thus, Sūta Gosvāmī defines the Absolute Reality (tattva) as nondual consciousness ( jñānam advayam).

The Lord’s body and its limbs are each fully conscious and potent, and, therefore, nondifferent from Him.

For this reason it is said that in Śrī Kṛṣṇa there exists no difference of the svagata-bheda type.

Even when the original Supreme Lord (Svayaṁ Bhagavān) expands into forms such as Rāmacandra and Balarāma, these svāṁśa (selfsame) expansions remain nondifferent from Bhagavān’s original Self. Still, while He is not dependent on Them, They are dependent on Him. Since Bhagavān and His svāṁśa expansions belong to the same class, no difference of the sajātīya-bheda type is found in Him.

Material nature, being inert, belongs to a class of existence different from that of the transcendent Personal Absolute. This might lead one to conclude that there is vijātīya bheda between Him and material nature. Nevertheless, since material nature’s existence is not independent or separate from Him, there is ultimately no difference of vijātīya-bheda between Him and His material expansions.

Energy cannot exist without its source, nor is it completely different from its source.

The finite living beings belong to the intermediary potency of Bhagavān. Thus, one may view them in two ways, as belonging to the same class as Bhagavān, because they are conscious like Him, or as belonging to a different class, because their magnitude and potency are infinitesimal.

From both viewpoints, the jīvas are fully dependent on Bhagavān, so there exists none of the three types of difference between them and the Lord. Śrīla Jīva Gosvāmī concludes, therefore, that although Bhagavān’s energies serve Him in various ways, they have no existence separate from Him(taṁ vinā tāsām asiddhatvāt). Just as a spider weaves a webwith a special substance it produces from its mouth and then makes the web its home, so Śrī Kṛṣṇa, the personal nondual Absolute Reality, employs His own energies to manifest the spiritual realm, where He resides. These energies are part of His intrinsic nature and have no independent existence.

In the Bhāgavatam verse under discussion (sb 1.2.11), the word jñāna, which ordinarily means “knowledge,” refers to “consciousness.” Here, however, consciousness does not imply devoid of content, i.e., without the divisions of subject and object.

Its significance here is that Nondual Reality is purely of the nature of consciousness and is also conscious, just as the sun is entirely of the nature of light and is also luminous.

Because the word jñāna refers to Absolute Reality, this nondual consciousness must have perpetual existence (sat) as a characteristic. And because the word tattva indicates the supreme objective of life, it follows that this Nondual Reality must also be characterized by bliss (ānanda), since all living beings seek pleasure, whether they know it or not.

From direct perception, logical analysis, and scriptural authority, we can understand that the ultimate motivation in all activities is the pursuit of joy. This is the basic purpose underlying creative and destructive processes and all personal relationships. As the Bṛhad-āraṇyaka Upaniṣad states, “My dear, the husband is not loved for his own sake, but for the sake of the Self” (na vā are patyuḥ kāmāya patiḥ priyo bhavaty ātmanas tu kāmāya patiḥ priyo bhavati, bau 2.4.5).

Here the word “Self” refers either to the individual self (the ātmā) or to the Supreme Self (Paramātmā). The verse is saying that in reality it is the Self alone that is dear.

In the conditioned state, the self we perceive is the empirical self, the jīva.

We become attached to someone or something not primarily because of their own dearness, but because we derive happiness from loving that person or thing.

This feeling of happiness comes from our egoic sense of selfappropriation— the notion that the object of love is “ours”— not from the person or the object itself.

The truth of this principle is shown by the common sense observation that the intensity of pleasure derived through material experience naturally decreases as the degree of identity with those experiences diminishes.

By contrast, in the liberated state, one realizes the true self as a servant of Bhagavān. When we act solely on the basis of this understanding, we become pure devotees of Bhagavān, and then we render service only for His pleasure, desiring nothing in return. Even if the all-attractive Lord treats us roughly, we remain established in devotion, abandoning all fears and cares in our loving relationship with Him. Śrī Caitanya demonstrated this standard when He prayed:

āśliṣya vā pāda-ratāṁ pinaṣṭu mām adarśanān marma-hatāṁ karotu vā

yathā tathā vā vidadhātu lampaṭo mat-prāṇa-nāthas tu sa eva nāparaḥ

Kṛṣṇa may embrace me or trample me under His feet,

or He may break my heart by being away from me.

He, a debauchee, may treat me as He likes,

yet He alone is my very life and no one else.

(Śikṣāṣṭaka 8)

In conditioned life, we do not know that Kṛṣṇa is the supreme object of love and the source of all bliss. Rather, we mistake ourselves for the source of bliss.

To enlighten us about Himself, Kṛṣṇa instructs us in Bhagavad Gītā:

ahaṁ sarvasya prabhavo mattaḥ sarvaṁ pravartate

iti matvā bhajante māṁ budhā bhāva-samanvitāḥ

mac-cittā mad-gata-prāṇā bodhayantaḥ parasparam

kathayantaś ca māṁ nityaṁ tuṣyanti ca ramanti ca

I am the source of everything. All things and actions emanate from Me.

Knowing this, the wise, full of love for Me, worship Me.

With their attention focused exclusively on Me and their lives entirely submitted to Me, they derive great satisfaction and relish always enlightening one another and conversing about Me.

(gītā 10.8–9)

Thus, there is an inherent relationship between jñāna (consciousness), sat (eternal existence), and ānanda (bliss). This relationship is clearly indicated in such Śruti statements as, “Brahman is pure consciousness and bliss” (vijñānam ānandaṁ brahma, bau 3.9.34).

Thus, the nature of the nondual consciousness described in this verse has been designated sat-cit-ānanda, “eternal being, consciousness, and bliss.”

In this anuccheda, Jīva Gosvāmī presented his thesis that jñāna is eternal. In the next anuccheda, he will state the pūrva-pakṣa, or the opponent’s objection that consciousness is momentary.

He will then present the rebuttal to this view.

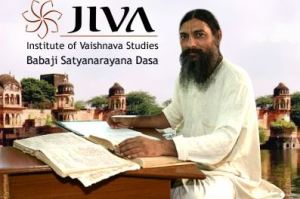

(Srila Satyanarayana das Babaji)